Finding User Sessions with SQL

Benn Stancil, Co-founder & Chief Analytics Officer

March 20, 2015

NaN minute read

A lot of product questions are based on the idea of a user “session.” What do users do when they first log in? In what order do users take specific actions? How long do people use your site in an average sitting? Does activity vary by device?

A number of analytics tools define user sessions automatically. But, default definitions may not be appropriate for your unique product or, even if they are, there will be times you'll want to define sessions using your raw event data. This can seem daunting—but it doesn't need to be.

What's a User Session?

A user session is a period of uninterrupted activity on a website or app. If a user opens Facebook, clicks around the timeline, looks at a few pictures, and then closes Facebook, that would be one session.

This definition, however, is imprecise. What exactly is a user? What constitutes activity? What does uninterrupted mean?

Depending on what you're analyzing, these questions have different answers. Facebook might define a user as someone who's logged in, while the New York Times considers everyone looking at a page. Activity on YouTube likely includes the time a video is playing, but Amazon might require people to click on things to be considered active. And while Netflix might allow long breaks in activity and still consider it uninterrupted—pausing a movie to go to the bathroom probably shouldn't start a new session—Snapchat might break up sessions if someone stops using the app for just a couple minutes.

Moreover, even within a single product, these definitions can change depending on the question you're trying to answer. Facebook's Messenger app is likely opened and closed repeatedly during conversations. In some cases, Facebook might want to consider the back-and-forth during a single conversation as one session, regardless of how many times the app was opened or closed. In other cases, they might want to end the session when the app is closed and start a new one every time it's opened.

Unfortunately, most tools that automatically define user sessions provide default answers to these questions. Google Analytics, for example, automatically makes assumptions about what user activity is, and how much time must pass between activities to constitute new sessions.

Because your product may not fit within these defaults—or only fits sometimes—it can be useful to define sessions manually. While it might seem complicated, it's actually straightforward to define custom sessions when working with raw data.

Defining Sessions with SQL

To define user sessions using SQL, all you need is a table of event data and a database that supports windowing functions(which, notably, excludes MySQL). Though these tables typically include a lot of information—user IDs, timestamps, event names, static IP addresses, browser and device info, and referral paths—the only two columns you need for defining a session are a user_id column and a timestamp of when an event took place.

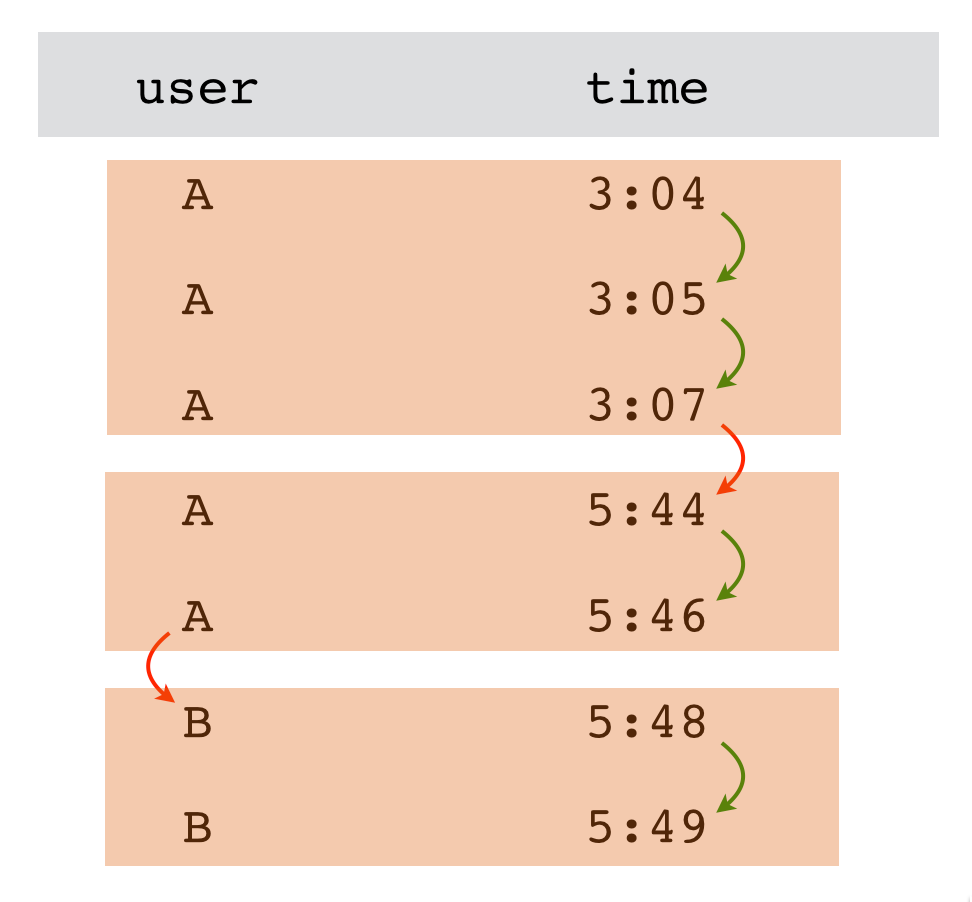

The following illustration provides an overview of how the queries outlined below will calculate sessions. You'll look at the actions taken by a particular user, and search for gaps between an action and the subsequent action. You'll then define the gap size that initiates a new session.

Finding the Start of Every Session

The first step for defining sessions is figuring out when new sessions start. If all you're looking to do is count sessions, this will be the only step you'll need. If you're looking to analyze what a user does during each session, however, you'll need to map each event to its appropriate session (more on that below).

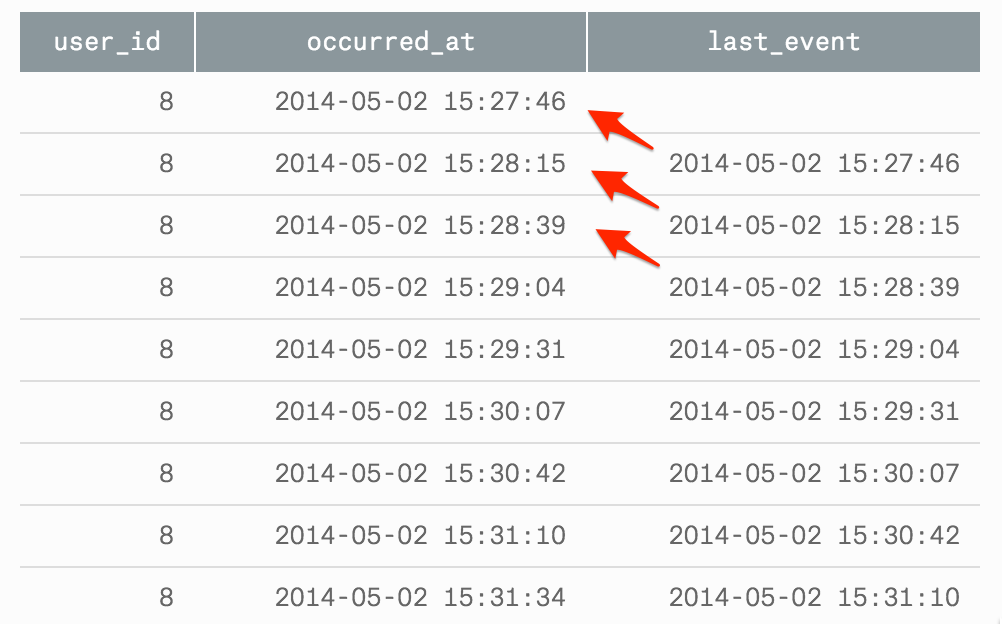

The query to define the beginning of a session starts by adding a column to your events table that shows the timestamp of the user's previous event. This can be accomplished easily with the LAG function.

SELECT *,

LAG(occurred_at,1) OVER

(PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at) AS last_event

FROM tutorial.playbook_eventsThe function returns the previous occurred_at value for the user_id. Importantly, if there is no previous value (i.e., you're looking at the row with the user's earliest occurred_at event), the function will return a null value. Note that in the result, the last_event timestamp matches that of the previous event.

If there are events in your events table that might get logged even when a user is inactive (for example, autosave events that get logged automatically at regular intervals), you can filter these events by simply adding a WHERE clause to your query.

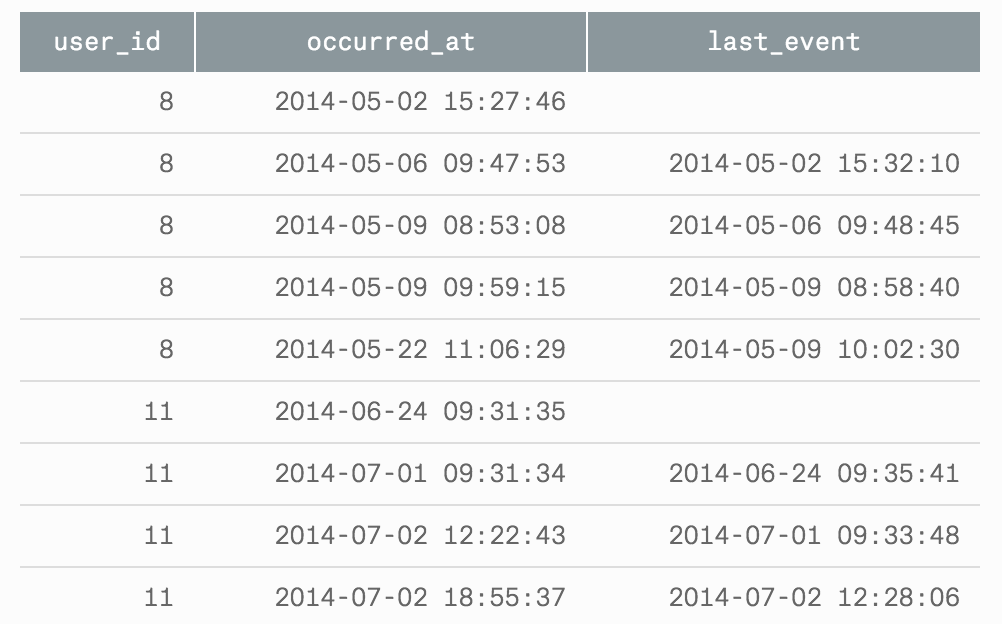

The next step is to figure out how long you want breaks between sessions to be. For products that are used briefly and often, you may want a new session to start after five minutes of inactivity; for more in-depth products, it may be an hour. As a benchmark, Google Analytics defaults to 30 minutes.

Let's assume you picked ten minutes for this value. The next step in your query is to only include events that occurred at least ten minutes after the previous event. To do this, wrap the last query in an outer query and add a WHERE clause.

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT *,

LAG(occurred_at,1) OVER

(PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at)

AS last_event

FROM tutorial.playbook_events

) last

WHERE EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM occurred_at)

- EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM last_event) >= (60 * 10)

OR last_event IS NULLThe EXTRACT pulls parts of a date out of timestamp. In this case, it's extracting the timestamp's “epoch,” which is the number of seconds since January 1, 1970. Because the dates are converted to seconds, the ten minute interval has to be converted to seconds as well.

To make sure you return the very first event a user logged, also return rows where the last_event is null.

Mapping Every Event to its Session

Often, finding the start of every session isn't enough to answer your question. If you want to know what a user is doing during each session or how long the session lasted, you'll need to map every event in your event stream to the session in which it occurred.

Your first instinct may be to join the table above to your full event table and map events to sessions by inserting them between the start and end time of the corresponding session.

This method works, with just a few additions to the query above. In fact, when I first tackled this problem, I used this exact approach. But JOINs, especially on large event tables, are really expensive to compute. Luckily, there's a way to get the same result without any joins.

A join-less method was first shown to us by a friend from the Yammer days, Elliott Star. His first step is the same as above: write a query with a LAG function to find the timestamp of the previous event.

SELECT *,

LAG(occurred_at,1) OVER

(PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at) AS last_event

FROM tutorial.playbook_eventsNext, in the outer query, add a case statement that returns a 1 for every event that starts a new session and a 0 for all others. This is simple; it's just moving the WHERE clause from the previous version into a CASE statement.

SELECT *,

CASE WHEN EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM occurred_at)

- EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM last_event) >= (60 * 10)

OR last_event IS NULL

THEN 1 ELSE 0 END AS is_new_session

FROM (

SELECT *,

LAG(occurred_at,1) OVER

(PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at)

AS last_event

FROM tutorial.playbook_events

) last

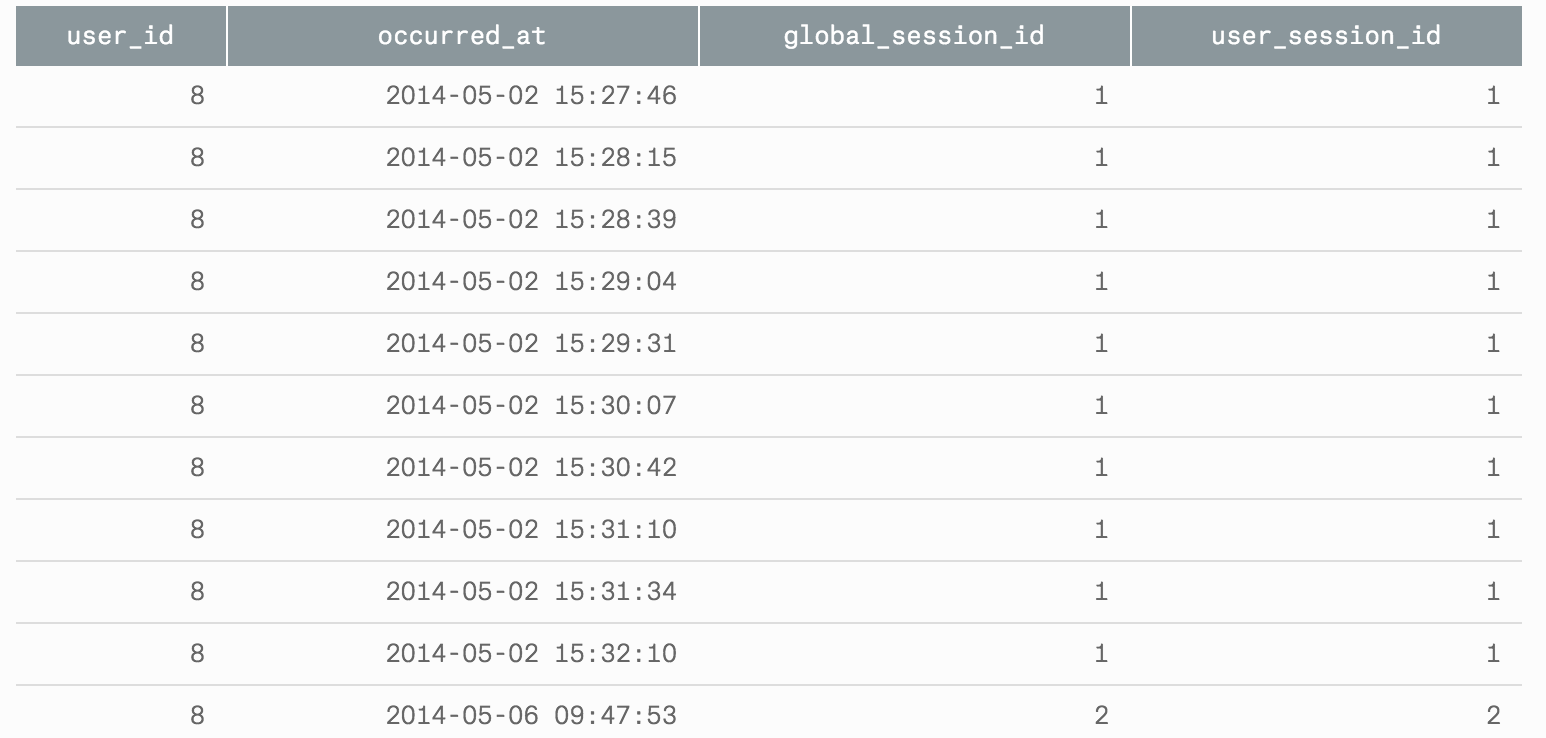

The final step is the clever one. If you order your table correctly, the running total of the is_new_session column will map perfectly to the session in which the event occurred, returning a unique value for every session. By partitioning your running total by user, you can also create a user_session_id that's unique to that user.

SELECT user_id,

occurred_at,

SUM(is_new_session) OVER (ORDER BY user_id, occurred_at) AS global_session_id,

SUM(is_new_session) OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at) AS user_session_id

FROM (

SELECT *,

CASE WHEN EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM occurred_at) - EXTRACT('EPOCH' FROM last_event) >= (60 * 10)

OR last_event IS NULL

THEN 1 ELSE 0 END AS is_new_session

FROM (

SELECT user_id,

occurred_at,

LAG(occurred_at,1) OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY occurred_at) AS last_event

FROM tutorial.playbook_events

) last

) final

LIMIT 100

Once you create this table, it's easy to figure out the average length of a session, the number of times people take a particular action during a session, and answers to many other questions you might have.

Applying these methods to BigQuery, Segment SQL, and Snowplow

If you'd like to use any of these queries on your own event data, you can simply clone the reports and adapt the table names to fit your schema. If you record your event data using a third party like BigQuery on Google Analytics, Segment SQL, or Snowplow, we've put together examples of how to adapt these queries to those schemas in this GitHub gist.

Questions? Drop us a line at hi@modeanalytics.com. We love hearing from you.

Recommended articles

Get our weekly data newsletter

Work-related distractions for data enthusiasts.